Australia’s Summer of Extremes: A Season of Severe Storms, Hail, and Cyclones

As summer comes to an end, we reflect on the major weather events that shaped Australia over the...

In the late hours of January 6, 1897, a cyclone developed near Port Darwin, striking the city in the early hours of January 7th. The peak of the cyclone was recorded at approximately 3:30-4:30am.

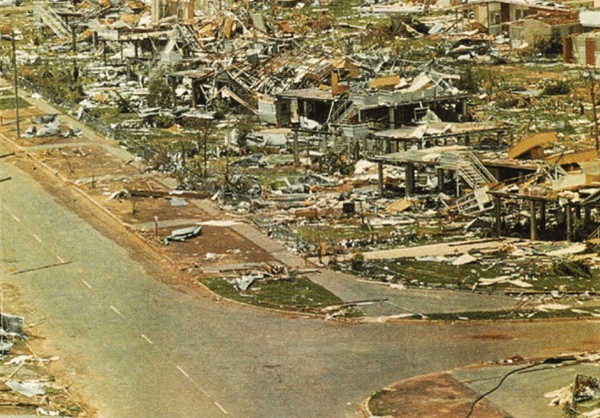

This was the largest cyclone recorded before Tracy; By approximately 7:30am, almost every building in Port Darwin had been destroyed. Eighteen pearling luggers, the government steam launch and three sampans were wrecked. Darwin recorded rainfall of 292 millimetres. Twenty-eight people were killed.

Complete devastation wrought by the January 6, 1897 Cyclone

87 years later, disaster struck again. For those old enough, none of us will forget the Christmas Day news of 25 December 1974. During the early hours of that day, Cyclone Tracy struck Darwin. Before the instruments failed, wind gauges registered speeds of 217 kilometres per hour rating this event at a minimum of Category 4. Over 80 per cent of all buildings were either destroyed or left seriously damaged. The cyclone resulted in the deaths of 71 people. Cyclone Tracy caused the largest ever evacuation and subsequent reconstruction operation in peacetime Australia. 35,362 people from a population of approximately 47,000 were evacuated to other cities for many months:

Christmas Day disaster. Cyclone Tracy 1974

In the Northern Territory, the weather, and by extent climate risk, is nearly always measured within the extremes. The Monsoons, the build up of heat and humidity as the season arrives, the cyclones and the almost daily thunderstorms which crash across the landscape are ever-present reminders of what nature can unleash. Mapping and measuring historic events is critical to mitigating risk in the future. What has happened in the past can happen again. Spatialising and measuring the frequency and magnitude of these climate risks provides the platform to predict the future and take action today to avoid the inevitable impact of extreme perils.

The ‘Top End’ of Australia is an essential element of Australia’s history and future. It’s impossible to tell the story of Australia without featuring the Top End. In turn, as the country looks to build a new and dynamic identity for itself in the 21st century which is seeing the challenges of climate risk interwoven with immense opportunities arising - especially within the Asian region which is experiencing the fastest economic growth in the world - the Top End is shaping up as a key stepping stone to build upon in this new era.

Yet despite the importance of the Top End to Australia, the fact is it's not always as understood as it should be among the general public. There are many reasons for this, but the end result is in order for Australia to really put its best foot forward in the years to come, it’s essential that a greater understanding is gained of what makes the Top End so special, and how mitigating Australia’s unforgiving extreme weather should play a key role in shaping plans and policies in the time ahead within the public and private sector alike.

At the outset, it’s necessary to recognise that while Australians will all have a general picture in mind when someone cites the Top End, in actuality its precise boundaries can vary somewhat depending on who is defining it. That’s why it’s prudent to commence here with a quick note discussing some of the different definitions, and which one we shall be utilising here in subsequent sections.

The Top End is commonly defined as the northernmost reaches of the Northern Territory. It encompasses well-known locales like Darwin, Arnhem Land, the Katherine region, and Kakadu National Park. Because Queensland’s Cape York is actually the northernmost point of the mainland, sometimes when Australians refer generally to the ‘top part’ or the ‘northern end’ of Australia they may well be discussing Queensland, the Northern Territory, or both. But generally, the Top End is understood to mean locales within the northern part of the Northern Territory exclusively, and it’s this definition we shall be proceeding on with.

The debate surrounding the arrival of human beings at various times throughout history to Australia has been ongoing. For instance, while the arrival of the British is of course very well-known, the encounters with the land prior by the Dutch and the French - in addition to evidence suggesting the Portuguese may have visited prior to the British - all affirm the challenging nature of defining precise dates in history. It’s widely recognised and understood that the history of Aboriginal Australia is thousands upon thousands of years old - and the arrival of their peoples pre-dates all others by many millennia - yet there has been enduring debate about just how old it is. Recent research suggests Aboriginal Australians first landed in the Top End more than 65,000 years ago.

Accordingly, Aboriginal Australians are held to be the oldest civilisation in history whose existence has persisted from establishment up until today. It is believed by scientists based upon archaeological evidence that Aboriginal Australians arrived from islands north of Australia, and this is further affirmed by the stories and traditions which Aboriginal Australians have passed down from one generation to the next. The Top End holds an incredible wealth of history surrounding the story of Aboriginal Australia, and continues to serve as a key area for enhancing greater understanding of Aboriginals, and the Australian landscape over many thousands of years.

When Australians reflect upon the military history of the country since Federation, the challenges Darwin faced in World War 2 - alongside a small-scale attack in Sydney Harbour during the same conflict - undoubtedly represent the most immediate and direct experience with danger faced by those residing on the mainland. Certainly, there were other struggles further afield such as the Gallipoli campaign of World War 1, and - in what is perhaps Australia’s most recognised conflict in World War 2 overall - the Kokoda Trail (AKA the Kokoda Track) campaign. Yet given these two campaigns took place off Australian shores, the Battle of Darwin (AKA the ‘Bombing of Darwin’) is commonly seen as Australia’s most direct experience in World War 1 and 2.

While today Darwin Harbour sees tranquil waves roll through it instead of the sound of combat, and Australians travel to the city to pay their respects instead of fleeing the dangers of the Battle, the events of 1942 remain a clear-cut example of Australia’s longstanding vulnerability and anxiety surrounding the defence of the Top End. The particulars of security policy when it comes to the likes of soldiers and submarines are best discussed elsewhere, but there’s no doubt in the 21st century the changes being seen surrounding the climate indeed pose a security threat to Australia, just as policies which seek to mitigate climate change risks offer avenues to enhance security overall.

Today the Top End is recognised domestically and internationally as one of Australia’s most wonderful regions. Arnhem Land represents Australia’s natural beauty at its finest, with 90,000 square kilometres of outstanding attractions across the entirely Aboriginal-owned land, with great fishing, tropical islands, and rainforests just a few of the many reasons travellers are lured to this part of the Top End. As a capital city, Darwin plays host to a rich dining scene that features fantastic cuisine from throughout Asia, alongside attractions like the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory.

In Katherine, incredible waterways are on display for visitors to explore by boat, canoe, and even by air, with regular scenic flights across the territory available. Then there’s Kakadu, the World-Heritage listed locale that holds a huge cultural and natural history, with amazing Aboriginal rock art, almost 300 bird species, and wonderful waterfalls. Effectively conserving these outstanding attractions for future generations requires action now to mitigate the growing risks of climate change.

In considering the Top End in its full context it’s necessary to recognise - for all the rich history and the romanticised identity which celebrates its rugged and remote aspects - there has indeed been an enduring dream to develop Australia’s northern reaches, and create a northern agricultural hub. Given such a dream is at least half a century old, it’s no surprise that there have been a number of different perspectives formed surrounding the best way to go about realising this goal, and accordingly what crops would feature specifically.

Nonetheless, there is no question that the way in which Australia currently utilises its vast amount of land within its northern reaches is set to change in future. Darwin is home to a globally significant liquefied natural gas (LNG) export hub. The Darwin LNG and Ichthys LNG projects supply over 10% of Japan’s annual global gas imports. The Northern Territory’s local projects include the US$37 billion INPEX-led Ichthys LNG Project, the US$5 billion ConocoPhillips-led Darwin LNG Project and the $800 million Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline.

This is coupled with the aspiration to see the installation of massive solar power farms which could not only provide renewable energy to Australia, but even be exported to those in need elsewhere in Asia. As a result, even if a greater development of the Top End has been a long time coming, there is unquestionably a new impetus in doing so, given the evolving nature of the Australian economy domestically, and rising demand for our agricultural exports among the rapidly growing populations across Asian nations.

It may be tempting for those who have doubts surrounding the potential for the Top End to be developed in this way to outright declare such a goal to be impossible. Yet the reality is - though certainly critique of such stated ambitions if unaccompanied by a legitimate foundation is fair - that it’s also worthwhile remembering other major goals for development in Australia were also critiqued before they were realised, only for history to then show the critics were indeed wrong. After all, there’s a certain famous bridge in Sydney that today is celebrated as a global icon of the city, yet had many seeking to stop its construction before it was built.

This article has illustrated why the Top End is a critical part of Australia’s past and future. Conserving its tremendous offerings for future generations requires action in this generation.

When it comes to mitigating the impact of climate risk, the next 10 to 15 years will be critical for public and private sector entities alike in the Top End, and around Australia more widely. The Early Warning Network features a team with expertise in meteorology, climate intelligence and spatial risk, offering round-the-clock monitoring of weather risks for our clients, and our staff are ready to provide the insightful data necessary for organisations to make informed decisions about operations in this 10 to 15 year time period.

To discuss how we can help your business call (02) 6674 5717, email support@ewn.com.au, or contact us via our enquiry page here.

As summer comes to an end, we reflect on the major weather events that shaped Australia over the...

While severe weather has hammered northern Australia over the past few months, the focus has...

Australia’s Tropical Cyclone season has officially begun, running all the way through until April...