Autumn Outlook and Summer Recap: Australia's Climate and Bushfire Preparedness

As Australia transitions from summer to autumn, it's essential to reflect on the recent climatic...

It has been a noticeably drier year across most of Australia so far compared to the last few years, particularly for the east, but what is the cause of the sudden shift from wet to dry conditions? Several major climate drivers influence rainfall and temperature patterns across the country, including the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) and Southern Annular Mode (SAM). Here, we take a look at each of them to help understand what is going on.

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation is the fluctuating between El Niño and La Niña phases, and is the most well known of the climate drivers. El Niño, which means 'Little Boy' in Spanish is considered the warm phase of the ENSO cycle, as the globe is typically hotter in El Niño events as the oceans release more heat. Conversely, La Niña means 'Little Girl', and is the cool phase of ENSO as the oceans hold in more heat.

In a neutral year (phases between El Niño and La Niña), trade winds blow from the east to the west due to the warm ocean temperatures in the western tropical Pacific Ocean and relatively cooler waters (typically around 10 degrees difference) in the eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. Rising air and low pressure and rainfall occur over these warm waters in the western Pacific Ocean, whilst in the eastern Pacific high pressure and sinking air lead to dry conditions.

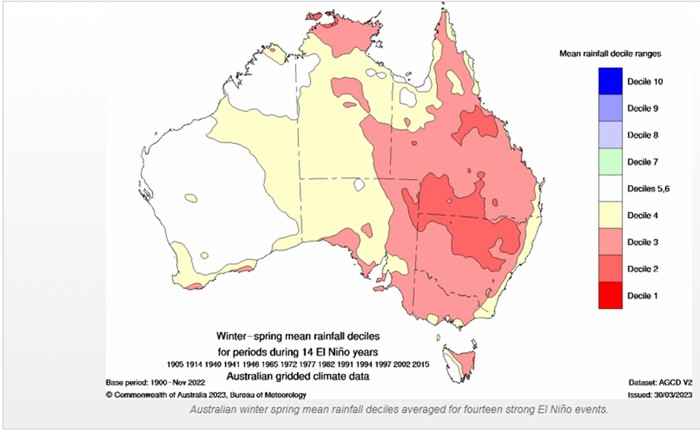

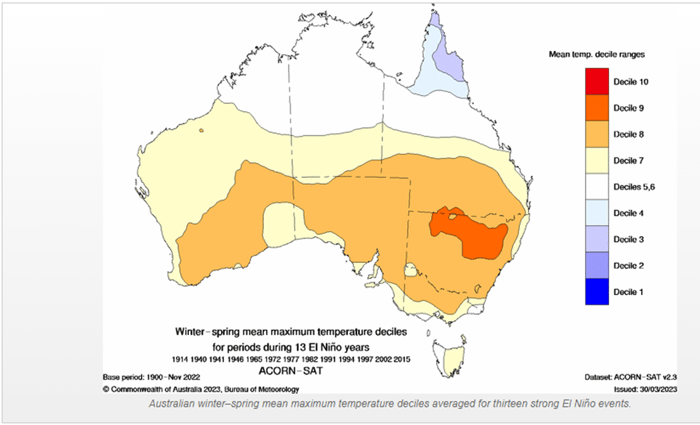

In an El Niño, waters become anomalously warm over the eastern and central tropical Pacific Ocean and the trade winds weaken or even reverse, causing increased rainfall and low pressure in the eastern and central Pacific Ocean, and reduced rainfall and high pressure over the western Pacific Ocean, including Australia (particularly eastern and northern parts).

Figure 1. Winter-spring mean rainfall and temperature deciles in El Nino years (Source: Bureau of Meteorology)

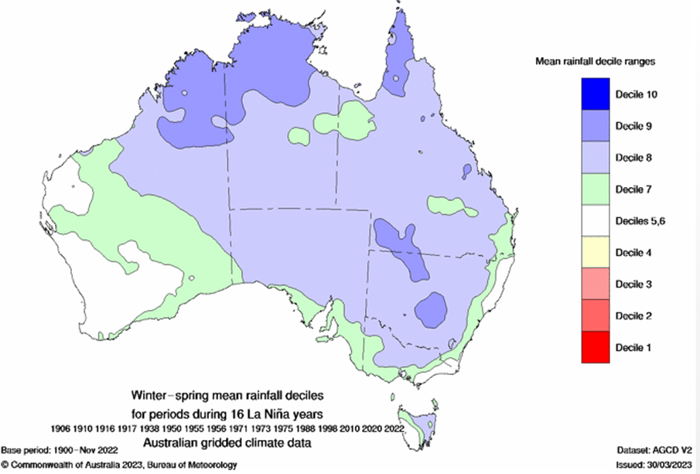

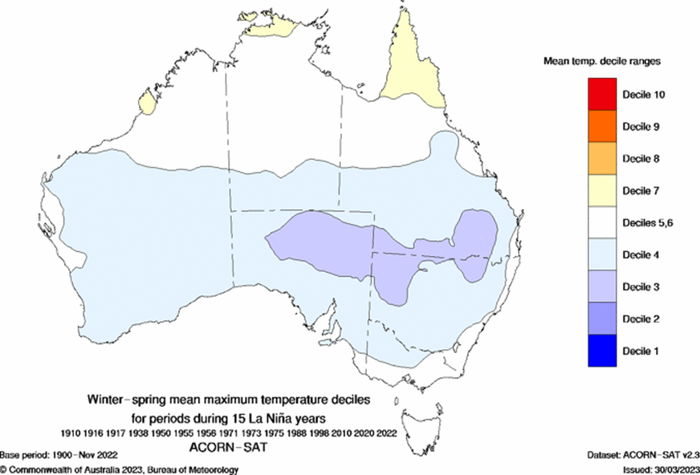

In La Niña, waters are anomalously cool over the central and eastern tropical Pacific, and anomalously warm in the western Pacific, leading to a strengthening of the trade winds and more rainfall and storms over Australia, but dry conditions and high pressure over the eastern and central Pacific Ocean.

Figure 2. Winter-spring mean rainfall and temperature deciles in La Nina years (Source: Bureau of Meteorology)

The Indian Ocean Dipole is another of Australia's major climate drivers, having a similarly strong impact on the climate as ENSO. The IOD is defined by the difference in sea surface temperature between a western pole in the Arabian Sea (western Indian Ocean) and an eastern pole in the eastern Indian Ocean south of Indonesia. Cycles are thought to be related to ENSO, with positive IOD events more likely in El Niño years, and negative IOD events more likely in La Niña years.

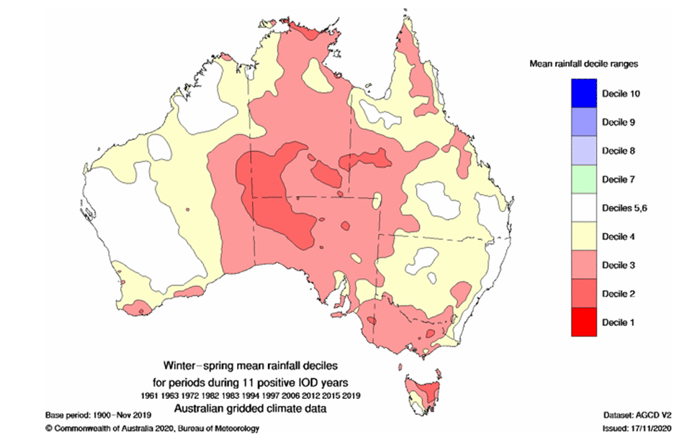

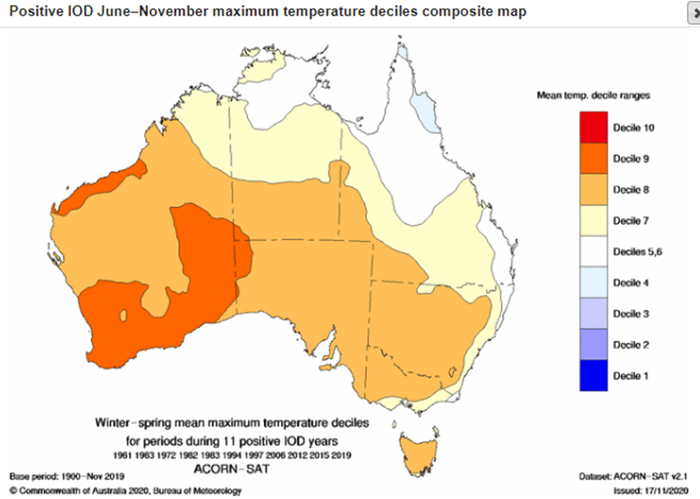

A positive IOD is characterised by warmer sea surface temperatures in the western Indian Ocean relative to the east, with easterly wind anomalies. Cooler than average ocean temperatures in the eastern Indian Ocean leads to sinking air and more high pressure, resulting in less rainfall across northwest and southern Australia, extending up to central QLD.

Figure 3. Winter-spring mean rainfall and temperature deciles in positive IOD years (Source: Bureau of Meteorology)

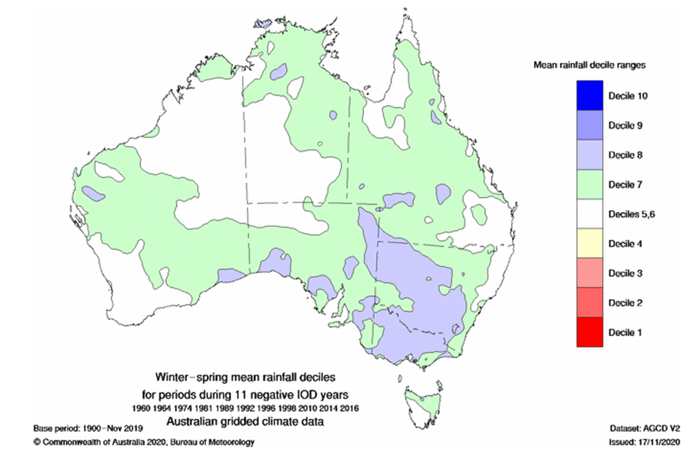

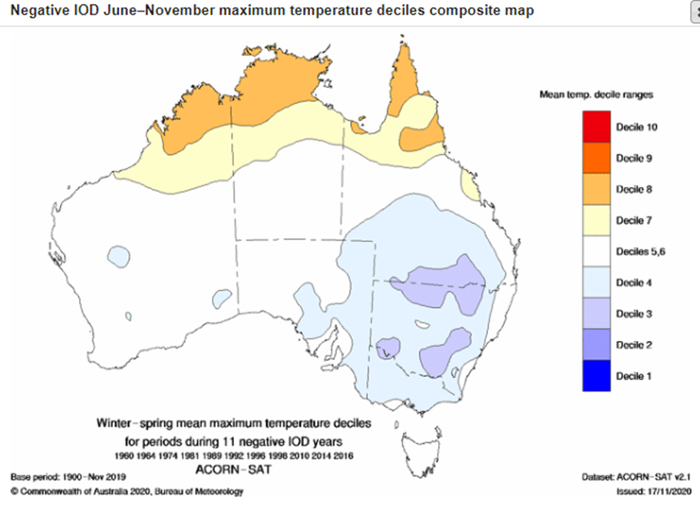

Meanwhile, negative IOD events are characterised by cooler sea surface temperatures in the western Indian ocean relative to the east. Winds become more westerly, bringing increase cloud and rain across northwest and southern Australia, extending into central QLD. Historically, these events have been linked to some of the wettest winters and springs on record.

Figure 4. Winter-spring mean rainfall and temperature deciles in negative IOD years (Source: Bureau of Meteorology).

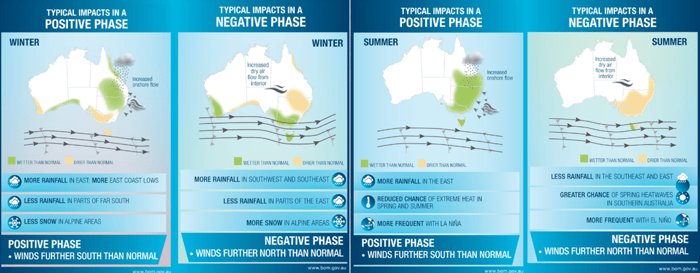

The Southern Annular Mode (SAM) is a climate driver that refers to the north-south movement of the strong westerly winds that blow in the mid to high latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere, and are associated with systems such as lows and cold fronts. It has three phases as well, but unlike the IOD and ENSO, phases tend to last on average one or two weeks. Regardless, variations in SAM can explain up to ~15% in weekly variances of rainfall, which is comparable to ENSO and the IOD.

Its influences are most pronounced in summer and winter, when the belt of westerly winds is either at their southern most or northern most, respectively. In winter, negative phases are characterised by increased rain and wind across southwest Western Australia, southeast South Australia, Victoria, southern New South Wales and Tasmania. However, reduced rainfall occurs across much of NSW and Queensland. A positive phase in winter generally has reduced rainfall across southern Australia, but increased rainfall over the north QLD coast, and some parts of inland NSW and QLD.

In summer, a negative SAM means generally dry weather for much of eastern and southeast Australia, except for western Tasmania. This can help fuel bushfire conditions if conditions have already been dry for some time. Meanwhile, a positive phase of SAM in summer can mean increased rainfall across the eastern half of Australia due to increased onshore winds.

Figure 5. Influences of the SAM on Australia’s climate in winter and summer in both negative and positive phases

(Source: Bureau of Meteorology)

Currently, the Bureau of Meteorology has Australia on an El Niño Alert, which means there is a 70% chance of an El Niño event developing in the coming months. However, other agencies in the world including the U.S. Climate Prediction Centre have already declared that an El Niño event is underway. So, why have some agencies declared an El Niño, whilst the Bureau of Meteorology has not?

It comes down to different criteria.

For the BoM to declare an El Nino event, any three of the following criteria need to be met:

Meanwhile, the U.S. Climate Prediction Centre's criteria to declare an El Nino is:

In short, the BoM's criteria are generally stricter and requires the atmosphere to show the typical El Nino signs that it's working together with the ocean in a process called coupling. This often results in other international agencies calling an El Nino before the BoM.

Currently, trade winds across the Pacific Ocean remain close to average, whilst the Southern Oscillation Index has shifted back to neutral recently after a couple of months of strongly negative values. However, looking further ahead the majority of climate models indicate an El Nino event to develop over the next few months. Models also suggest a positive Indian Ocean Dipole event may develop in the next month or two, although the strength of this event remains uncertain at this stage.

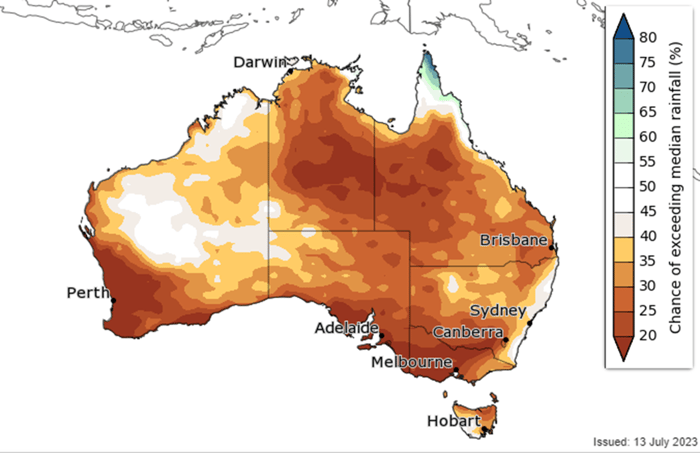

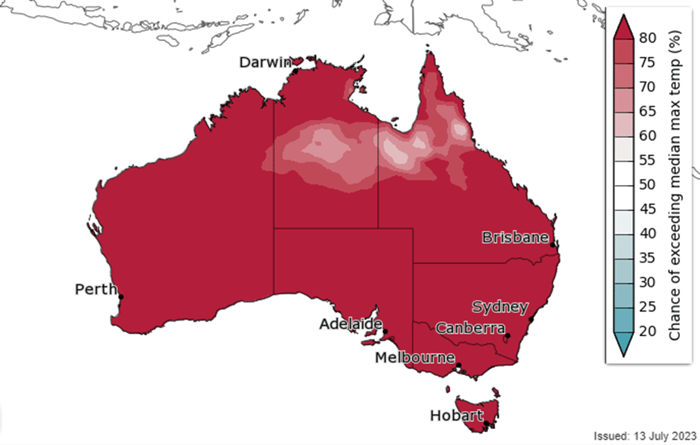

Figure 6. Bureau of Meteorology outlook for rainfall (left) and maximum temperatures (right) for the August to October period

(Source: Bureau of Meteorology)

Both an El Niño and positive Indian Ocean Dipole would mean bad news for Australia, with dry conditions persisting through the end of winter and into spring. With large fuel loads across the country from three consecutive wet years, this will increase the risk of bushfires in spring and summer.

El Niños typically have less influence over the climate in summer and tend to begin to breakdown later in the season or early autumn. Indian Ocean Dipole events tend to break down as the monsoon develops.

It is likely that the BoM will declare an El Niño event this year, but exactly when remains to be seen.

As Australia transitions from summer to autumn, it's essential to reflect on the recent climatic...

Australia’s Tropical Cyclone season has officially begun, running all the way through until April...

Climate risk and other natural hazards are a recurring nightmare for governments, as they can...